Crossing the Border: Into Ethiopia, Sudan, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Uganda and Kenya

Seeking Refuge and Asylum

Crossing The Border

Into Ethiopia and Sudan

The largest numbers of Eritrean refugees have escaped by land. When they have first crossed an overland border, their experiences have differed, depending on whether they have fled to Ethiopia, Sudan or elsewhere. Each of those two countries, working in concert with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), for many years commonly accepted the arrivals as lawful, or at least as “prima facie,” refugees. But the refugees’ circumstances have remained fragile, and shifting. The savage civil wars in Tigray, Ethiopia (2020-2022) and in Sudan (from 2023 into 2025), in particular, have wreaked mayhem on the Eritrean refugee communities there and have caused many of their members to flee again, for their lives.

Sudan

In recent years some refugees in Sudan were kidnapped en route to refugee camps, en route to or in major urban centers, or even within the camps themselves. The kidnappers were either traffickers who would sell the hostages for purposes of extortion and torture, or Eritrean agents who would drag the hostages back to Eritrea to be imprisoned, tortured or killed. In early 2015, UNHCR reported that almost all female survivors of the trafficking in Sudan whom it had identified in 2014 had been sexually assaulted or raped. Of great concern were reports, continuing through at least 2017, that the Sudanese government itself, sometimes through its notorious Janjaweed militias (later reconstituted and officially embraced by the government as the Rapid Security Forces [RSF]), had been arresting Eritrean refugees and refouling, or deporting, them back to Eritrea, where a dire fate awaited them. In mid-2017, reports of significant numbers of Eritreans so arrested and refouled arose repeatedly. During the vicious civil war in Tigray, Ethiopia between 2020 and 2022, and the Eritrean army’s attacks on Eritrean refugee camps there in 2020 and 2021, large numbers of Eritreans living in Tigray fled to an insecure existence in Sudan. In 2022 and early 2023 (if not before), Sudanese police frequently arrested, detained and extorted for cash Eritrean refugees living in the capital, Khartoum, and sometimes in eastern Sudan.

In mid-2023, when a horrific armed conflict between the RSF and Sudanese government troops (the Sudanese Armed Forces [SAF]) began, the police appeared to have stopped abusing the refugees. But the RSF – soon in control of Khartoum – picked up where the police had left off: robbing, raping and killing Eritrean refugees there. Many fled to Eastern Sudan, where Eritrean refugees had lived for several generations. But there Eritrean agents — with the apparent complicity of Sudanese authorities — began kidnapping the newly arriving Eritrean refugees (those from Khartoum) and abducting them to Eritrea, to meet an uncertain fate. In April alone, reportedly 3500 Eritreans were so abducted. Other Eritreans fled from Sudan to South Sudan, Uganda, Chad and Egypt, often in the process encountering obstructions by receiving governments as well as acute mortal peril. Many more fled to Ethiopia, where they (together with Sudanese refugees) were received in several new UNHCR camps near Sudan’s border. However, health and security conditions in those camps were appalling: cholera outbreaks were common and local residents frequently robbed and attacked the refugees. As a consequence, many Eritreans fled onward to Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa or to Kenya. But in Addis the Ethiopian government forbade them from enjoying UNHCR registration, support and protection; and Kenyan police often arrested and jailed them, sometimes colluding with smugglers. Meanwhile, by 2024, the Eritrean government had allied with the SAF against the RSF (described in this website at The Repression Avalanches: Eritrea in Sudan, Again) — to the point of establishing a military presence in and training pro-SAF troops within Eastern Sudan. There the Eritrean refugees that remained in Eastern Sudan became vulnerable to potential attacks by Eritrean forces such as had occurred, with devastating effect, at the Eritrean refugee camps in Tigray.

Ethiopia

In June 2018, Ethiopia and Eritrea embarked on a radically new and hopeful peace initiative between the two countries. In September 2018 their border was officially opened, which resulted in many thousands of Eritreans fleeing to Ethiopia. The border closed again, but it became more porous, and thousands have continued to flee. Many of those fleeing appeared to wish to stay in Ethiopia, while others seemed bound for neighboring countries and Europe. At least to an extent, the trafficking abuses occurring in Sudan have appeared to afflict those undertaking forward migration from Ethiopia as well.

Those who arrived in Ethiopia had long been relatively safe there. But following the rapprochement with Eritrea, many refugees came to fear that the Ethiopian government would refoule them to Eritrea through some arrangement with the Eritrean regime. In addition, beginning in early 2020, with some exceptions, Ethiopia stopped granting prima facie refugee status to newly arriving Eritreans. At least some of the new refugees did not have ready access to the refugee camps, and thus, reportedly, they had become homeless and destitute.

And then, in November, came the war in Tigray – when the Ethiopian government encouraged Eritrean forces to enter that Ethiopian region and wage barbaric war on the Tigrayans. The Ethiopian government also allowed the Eritrean forces to horrifically abuse the Eritrean refugees in Tigray and elsewhere in Ethiopia. That savage violation of international law and the devastating impact on Eritrean refugees is described by The America Team here and below on this page under “The Trying Life in a Refugee Camp.”

The Tigray war ended in November 2022. But since then, Ethiopia has continued denying refugee status to newly arrived Eritreans, thus making it both difficult to subsist there and difficult to move on to another country; and in June 2023 Ethiopia deported hundreds of Eritrean refugees to Eritrea — a gross violation of international law — all as described by the United Nations here.

In addition, Eritrean refugees who, during the war, had fled from Tigray to a UNHCR facility in the Amhara Region called Alemwach continued, through late 2024, to suffer kidnapping, extortion, theft, assault and murder at the hands of Amhara residents and even Alemwach’s government-supplied guards, as described here.

The circumstances of the refugees in Ethiopia continued to deteriorate. The Ethiopian government proposed in November 2024 to move an unspecified number of Eritrean refugees to a new camp to be built in the inhospitable and insecure Afar Region, as described here. And following weeks of increasing government harassment of Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa by way of detention and extortion as described here, in December 2024 the government began, once more, rounding up large numbers of Eritreans in Addis and sending them north to Eritrea — yet again violating international law.

So altogether, Ethiopia was no longer a safe haven for Eritrean refugees; but those who already lived there were trapped, with most having no other place to safely flee.

Into Djibouti and Saudi Arabia

Indeterminate numbers of Eritreans have escaped their country into Djibouti. Tens of thousands of Eritreans have migrated to Saudi Arabia, where they were initially welcomed as guest workers and their passage was facilitated by the Eritrean government. But thousands have now been subjected to punitive Saudi taxes and have become either trapped in or forced out of the country, with many fleeing to Egypt, Uganda, Ethiopia and Sudan. Refugee and asylum status are not available in either Djibouti or Saudi Arabia.

Into Yemen

Some Eritreans have escaped their country by boat, across the Red Sea, to Yemen. In the spring of 2015, as the security of Yemen disintegrated due to that country’s sectarian civil war, Eritrean refugees came to be stranded there, at great peril to their lives. Many were and remain without work, without adequate food, endangered by the military hostilities, and unable to leave the country. Many are afraid to walk on the streets, for fear of kidnapping or of injury from military actions. As in Djibouti and Saudi Arabia, refugee and asylum status are not available.

Into Kenya and Uganda

For many years, some Eritreans have fled southward, to Kenya (from Ethiopia) and to Uganda (from Kenya). Since the civil war in Sudan began in 2023, a wave of Eritreans who had been living in that country or in Ethiopia have fled to Kenya and Uganda.

Kenya

The reception of Eritrean refugees in Kenya has been mixed. Most have settled in urban areas, where local and international assistance is limited. In the 2020s, Eritreans have been arrested and deported from time to time — including some who have claimed to have been en route to South Africa. From 2023 into 2025, new Eritrean arrivals in Kenya, driven there by the war in Sudan, have had difficulty registering with or being assisted by Kenyan authorities as refugees; and in July 2025 registration of new Eritrean asylum seekers was formally suspended, as were applications by refugees to live outside of designated areas. They have often been denied opportunities for resettlement in third countries, detained, extorted for ransom by traffickers and police, and threatened by governmental authorities with deportation to Ethiopia or Eritrea. As recently as November 2024 some Eritreans who had arrived years earlier were imprisoned and extorted for ransom. Some who seek to flee Kenya for Uganda are extorted for ransom by the traffickers engaged to transport them.

Uganda

Uganda has been a happier home for Eritreans than Kenya. The first material migration to Uganda occurred during Eritrea’s War of Independence (1961-1991). The Eritreans eventually established a viable community there, particularly in the capital Kampala. Many of them founded small businesses, some of which came to enjoy good commercial relations with Eritrea. Thus, although many Eritreans in Uganda are impoverished, many have become comfortable, and many appear to be loyal to the Isaias regime. In May 2022 the Eritrean community built its fourth (Orthodox) church in Kampala — a seemingly spectacular edifice. In December 2024 the Ugandan government welcomed a large conference of diaspora Eritrean investors in Kampala.

Refugees arriving in recent years have still been generally tolerated by Ugandan society, although (like urban refugees in many countries) often lacking adequate support from the host country, international organizations, and sometimes, in this case, even the prior waves of Ugandan arrivals. Endemic corruption compromises the refugee status and experience of many. In several instances in recent years, prominent Eritrean defectors — fearing violence or abduction at the hands of Eritrean agents operating within Uganda — lived miserably in secret locations for lengthy periods, unable to achieve resettlement in safer countries. Following the outbreak of civil war in Sudan, between 2023 and 2024 Ugandan government attempts to deport over 180 Eritreans occurred. In July 2024 over 150 Eritrean business people were arrested on grounds of trade infractions, possibly as scapegoats for Uganda’s internal economic difficulties. In January 2025 reports emerged that the new wave of arrivals from Sudan and Ethiopia was less welcome in Uganda generally, and that new registrations of Eritrean refugees could be suspended. Then in June 2025 the country reportedly barred asylum seekers from entering.

Seeking Refuge and Asylum

Rescue by the United Nations

In many parts of the world, UNHCR administers — or it helps the governments of countries of refuge to administer — sizable camps for refugees fleeing from nearby countries in turmoil. UNHCR does that in Ethiopia and Sudan, and several of the camps in those two countries are populated mainly or entirely by Eritreans. UNHCR conducts a number of operations in the camps and elsewhere in those countries of refuge. First, it seeks to provide physical shelter to the refugees, to protect them from harm, and to otherwise provide for their social welfare there. Second, it processes their claims to being legitimate “refugees” – individuals who, according to international law, have a “well-founded fear” of harm or persecution in their home countries for political or social reasons. Third, it seeks to achieve for those whom it has officially determined to be “refugees” one of three ultimate outcomes: having them fully absorbed in the country of first refuge, finding a third country that will absorb them, or eventually returning them to their home country when security conditions there permit.

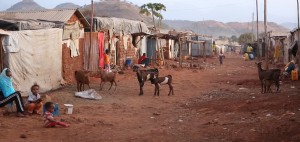

The Trying Life in a Refugee Camp

The resources of both UNHCR and the host countries have been severely stretched. At the refugee camps in Ethiopia and Sudan, living and security facilities have been rudimentary. Nutrition has been basic, sporadic, and not always adequate; sanitation, health care and educational resources have been uneven; women have been vulnerable to sexual abuse. While some refugees have sometimes been able to work in-camp within medical, construction, educational, commercial and other professions, most spend their days idly, endlessly, in what are typically bleak landscapes. As a consequence, camp residents have often been despondent – unable to work at a profession, restricted from or fearful of traveling outside of the camp, and feeling no hope for any of the three long-term resettlement outcomes that UNHCR seeks to achieve for them. Still, until 2020 their lives had been relatively secure.

The resources of both UNHCR and the host countries have been severely stretched. At the refugee camps in Ethiopia and Sudan, living and security facilities have been rudimentary. Nutrition has been basic, sporadic, and not always adequate; sanitation, health care and educational resources have been uneven; women have been vulnerable to sexual abuse. While some refugees have sometimes been able to work in-camp within medical, construction, educational, commercial and other professions, most spend their days idly, endlessly, in what are typically bleak landscapes. As a consequence, camp residents have often been despondent – unable to work at a profession, restricted from or fearful of traveling outside of the camp, and feeling no hope for any of the three long-term resettlement outcomes that UNHCR seeks to achieve for them. Still, until 2020 their lives had been relatively secure.

But beginning in November 2020 with the onset of the war in Tigray, as described on this page under “Ethiopia,” all of that was upended in the four UNHCR camps Tigray Province and one of the camps in its Afar Province. Hunger and massacre were rife. In Tigray, Eritrean forces destroyed two of the camps, and almost all of the Eritrean refugees there eventually fled to Sudan, to a new UNHCR facility south of Tigray in Amhara Province, to Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, or elsewhere. In Afar, as Tigrayan forces invaded, refugees fled the fighting and were scattered throughout the province, with the whereabouts of many of them long unknown.