Cursed if You Stay, Cursed if You Flee

Seeking Refuge and Asylum

Cursed if You Stay, Cursed if You Flee

The conditions in Eritrea today are excruciating. Yet for decades, with a brief reprieve in 2018-2019, its citizens have been generally forbidden from quitting the country. Those seeking to escape are considered traitors, and thus perpetrators of a capital crime. For years, Eritrean forces were instructed to shoot on sight any Eritreans trying to cross by land into Eritrea’s arch-enemy Ethiopia. Those seeking to leave in any direction have been subject to arrest, imprisonment and torture by the Eritrean regime if they were caught attempting to flee, as have been their families (in the case of those who succeeded in escaping) that had remained at home.

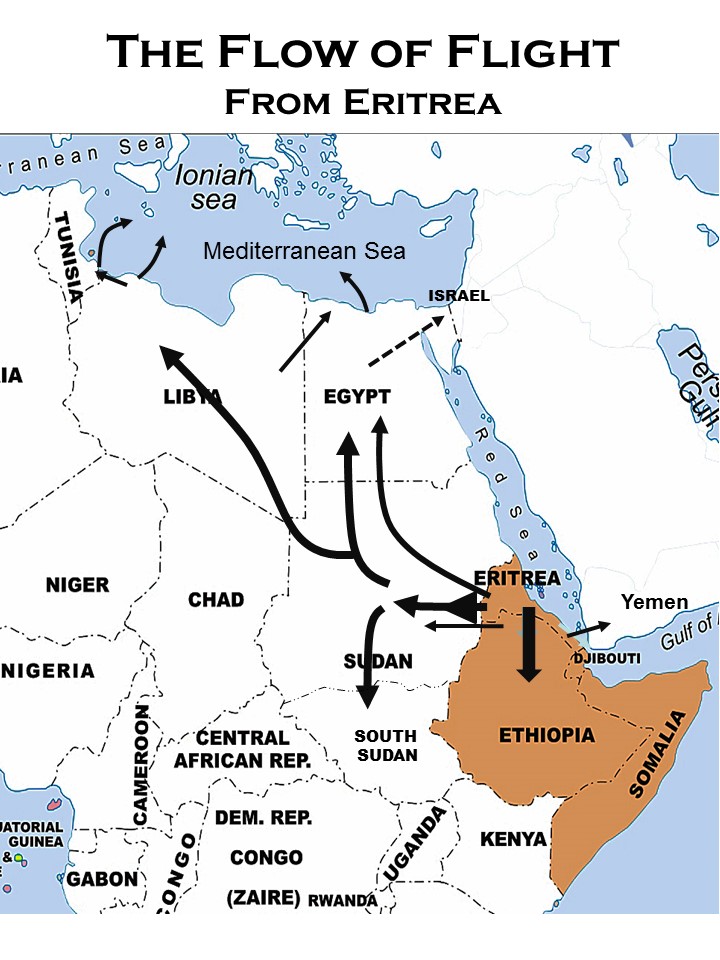

Still, hundreds of thousands have managed to escape – often young, bright adults, but also unaccompanied children who seemed to have little understanding of the world and little appreciation for the risks that lay before them. But even then, the trauma of their initial migration was often only beginning. They escaped into places that could be harsh and hostile towards them: particularly certain Arab-majority countries, where disdain, exploitation and brutality have frequently befallen sub-Saharan Africans; Israel, where brutality is not rife but the refugees are unwelcome by the current government and many citizens; and Europe, where a flood of Africans and Middle Easterners has tested that continent’s fundamental views about refugee protection. Since at least 2013, the mass drownings of Eritrean and other refugees in their attempts to cross the Mediterranean Sea into Europe have repeatedly captured headline news. Throughout this period, and particularly since 2020, Eritrean refugees in Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan and the Gulf States have been forced from one province or country to another, in what has become a perpetual state of not only displacement but grave privation and insecurity.

How did the escapees manage not to be shot at the border? The answer appears to lie within a complex web of circumstances: careful planning of escape times and routes; bribes paid to Eritrean border guards; engagement of smugglers connected closely to the Eritrean military; and the Eritrean regime’s own ambivalence — on the one hand seeking through terror to retain its citizens (especially educated ones and able-bodied soldiers), but on the other hand pleased to be rid of dissenters, pleased to receive the smuggling and bribery revenues, and pleased with the remittances ultimately sent by successful escapees to their families in Eritrea.

Portraits of Eritrean refugee life can be found in the section of this Web site titled Faces and Voices. Such portraits have not appeared widely in the American press. One exception is a compelling close-up — including the causes of flight, the conditions in Ethiopian refugee camps, the perilous passage across the desert and the Mediterranean for those who leave the camps, the challenges awaiting the refugees in Europe, and other topics addressed in this website — that was featured in The Wall Street Journal on February 2, 2016.