Refuge in the West, and Elsewhere

Seeking Refuge and Asylum

Refuge in the West, and Elsewhere

Welcoming the Refugees

A fortunate few of the Eritrean refugees manage to arrive in Western Europe or North America. They may arrive as official “refugees” — as designated and then referred to welcoming countries around the world by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) — although most countries accept no Eritreans as refugees at all, and those who do accept Eritreans place a limit on the numbers who may come. Individuals who come as refugees are entitled to and usually need to receive certain social services from the governments of the countries of refuge. The United States, for example, accepted between 1300 and 2600 Eritrean refugees per year between 2010 and 2017. Thereafter, under the Trump administration, the U.S. adopted more restrictive refugee admissions policies, and admissions plummeted. After that administration ended, admission levels were gradually restored. But the re-election of Trump in November 2024 virtually ensured that refugee admissions would drop once again. The U.S. provides refugees with social services through a network of non-profit refugee agencies around the country, many of them religiously affiliated. But overcoming language barriers, finding housing and work in troubled economies, and otherwise learning to live within a strange and highly modern environment are challenges that most refugees face and that the refugee agencies alone are unable to fully resolve.

A fortunate few of the Eritrean refugees manage to arrive in Western Europe or North America. They may arrive as official “refugees” — as designated and then referred to welcoming countries around the world by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) — although most countries accept no Eritreans as refugees at all, and those who do accept Eritreans place a limit on the numbers who may come. Individuals who come as refugees are entitled to and usually need to receive certain social services from the governments of the countries of refuge. The United States, for example, accepted between 1300 and 2600 Eritrean refugees per year between 2010 and 2017. Thereafter, under the Trump administration, the U.S. adopted more restrictive refugee admissions policies, and admissions plummeted. After that administration ended, admission levels were gradually restored. But the re-election of Trump in November 2024 virtually ensured that refugee admissions would drop once again. The U.S. provides refugees with social services through a network of non-profit refugee agencies around the country, many of them religiously affiliated. But overcoming language barriers, finding housing and work in troubled economies, and otherwise learning to live within a strange and highly modern environment are challenges that most refugees face and that the refugee agencies alone are unable to fully resolve.

Seeking Refuge and Asylum

Desperately Seeking Asylum

Some desperate Eritreans seek to avoid the indefinite, dismal existence that refugee camp life offers in Ethiopia and Sudan, preferring to forego the camps – or to move onward from the camps – and to hazard a journey into Western or other countries not as formally admitted refugees but without permission. Those who forego the camps altogether may not have an opportunity to be officially designated as “refugees” by UNHCR. Rather, they may escape directly from Eritrea by purporting to be regime loyalists, obtaining exit visas for the conduct of personal or professional missions abroad, and then defecting to the country to which they have traveled. Or from Ethiopia or Sudan they may steal into another country in contravention of that country’s immigration laws: such as somehow managing to get smuggled to Mexico and then crossing the border into the United States; or (far more commonly, and through a truly monstrous smuggling enterprise) setting out in small, crowded boats from Libya or Tunisia across the Mediterranean to one of Italy’s southerly islands, where they hope to proceed northward through Europe.

Some desperate Eritreans seek to avoid the indefinite, dismal existence that refugee camp life offers in Ethiopia and Sudan, preferring to forego the camps – or to move onward from the camps – and to hazard a journey into Western or other countries not as formally admitted refugees but without permission. Those who forego the camps altogether may not have an opportunity to be officially designated as “refugees” by UNHCR. Rather, they may escape directly from Eritrea by purporting to be regime loyalists, obtaining exit visas for the conduct of personal or professional missions abroad, and then defecting to the country to which they have traveled. Or from Ethiopia or Sudan they may steal into another country in contravention of that country’s immigration laws: such as somehow managing to get smuggled to Mexico and then crossing the border into the United States; or (far more commonly, and through a truly monstrous smuggling enterprise) setting out in small, crowded boats from Libya or Tunisia across the Mediterranean to one of Italy’s southerly islands, where they hope to proceed northward through Europe.

Whether defecting or stealing in, Eritreans, once in the West, often apply for “asylum” – protection and durable legal status – from the government of the country to which they have fled, on grounds of having a “well-founded fear” of harm or persecution for political or social reasons, as defined by international law. An asylum seeker can benefit greatly by receiving private legal assistance in pursuing his or her plea for safety with the government of the country of refuge. But private legal resources are not readily available to most refugees. And if they lose their asylum claims, they can be deported to Eritrea to face torture or death.

In Europe, the so-called “refugee crisis” that arose in the mid-2010s has actually been an “asylum crisis,” with millions of asylum seekers arriving from Africa and the Middle East without European permission. The huge number of arrivals has had enormous political and humanitarian consequences, with which European governments and humanitarians have been struggling mightily.

In the United States, until the re-election of President Trump in November 2024, several hundred Eritreans had been seeking asylum every year, many of them upon presenting themselves to U.S. authorities at the Mexican border. Most of those were prevailing in their asylum claims; but some — commonly because they lacked legal representation and/or because their cases were heard by judges generally indisposed to granting asylum — lost their cases and are slated for deportation. In addition, since early 2017, under the Trump administration, the U.S. government began materially restricting the availability of asylum for various nationalities generally — particularly for those who sought to enter across the Mexican border. With the end of that administration in 2021, entry and asylum restrictions loosened somewhat, and vast numbers of migrants (including a small number of Eritreans) surged northward in the U.S. Many or most of the migrants applied for asylum. Despite enormous backlogs in the processing of asylum claims, some Eritreans managed to win asylum, including, for example, 193 during U.S. fiscal year 2024. But President Trump’s re-election in 2024 was based to a considerable extent on his promise to end the migrant flow from Mexico and to tighten asylum eligibility — which seemed likely to impact Eritrean asylum seekers, along with hundreds of thousands of others, going forward. For example, since early 2025, the U.S.-Mexican border was effectively closed to migrants, and tens of thousands of migrants were being expelled from the country. The America Team’s guidance in support of Eritreans’ asylum claims in the United States appears here.

In September 2017, a disturbing development arose in the U.S.: immigration authorities determined to facilitate the deportation of some 700 Eritreans, many or most of whom had sought but were denied asylum. If they were returned to Eritrea, they would likely be tortured or executed. The America Team’s evaluation of the development, and its guidance for affected Eritreans, are found at this page.

As noted above, many people leaving Eritrea and its neighboring states seek (sometimes circuitously) to end up in the West – where the economies, however troubled, hold out hope for some form of employment, and where asylum procedures are well established. Other Eritreans, however, find themselves in Eastern Europe or countries across the Middle East, where they often are not welcome, not protected by international law, not given an opportunity to seek asylum, sometimes imprisoned, and sometimes returned (or threatened with return) to Eritrea. These individuals live in acute discomfort and fear.

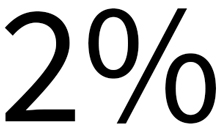

Harassment, Intimidation, and Extortion of the 2% Tax

The Eritrean government considers its worldwide expatriates – even refugees and asylum seekers who have fled the country – to continue to owe civic obligations to the Eritrean state. Secret Eritrean governmental agents pervade many countries of refuge, including in North America and Western Europe. There they have pressed the expatriates to obtain new government I.D. cards for which the expatriates must disclose extensive personal information; they have sought to control local Eritrean Orthodox churches, including in the United States; and they have intimidated the expatriates into paying an annual two percent income tax to the Eritrean regime, under threat — if they don’t pay — of imposing crushing fines and imprisonment on their families back home and denying them consular services and Eritrean records such as property deeds and birth, death and marriage certificates. In the Netherlands, Eritrean government agents have mounted a concerted campaign, including by bringing lawsuits, to intimidate Eritreans and others who are critical of the regime; Dutch authorities have resisted. Several Western governments have otherwise outlawed the intimidation and the tax collection; but others have acquiesced to it; and in all countries, whether legal or not, the practice appears to continue. A 2019 Amnesty International report detailed the harassment and intimidation that Eritrean regime operatives have mounted against regime critics in Europe, Africa and the U.S. In November 2024, The Washington Post exposed, in depth, the regime’s otherwise hidden fundraising operations in the U.S., despite the ongoing imposition of U.S. sanctions against the pertinent Eritrean entities.

The Eritrean government considers its worldwide expatriates – even refugees and asylum seekers who have fled the country – to continue to owe civic obligations to the Eritrean state. Secret Eritrean governmental agents pervade many countries of refuge, including in North America and Western Europe. There they have pressed the expatriates to obtain new government I.D. cards for which the expatriates must disclose extensive personal information; they have sought to control local Eritrean Orthodox churches, including in the United States; and they have intimidated the expatriates into paying an annual two percent income tax to the Eritrean regime, under threat — if they don’t pay — of imposing crushing fines and imprisonment on their families back home and denying them consular services and Eritrean records such as property deeds and birth, death and marriage certificates. In the Netherlands, Eritrean government agents have mounted a concerted campaign, including by bringing lawsuits, to intimidate Eritreans and others who are critical of the regime; Dutch authorities have resisted. Several Western governments have otherwise outlawed the intimidation and the tax collection; but others have acquiesced to it; and in all countries, whether legal or not, the practice appears to continue. A 2019 Amnesty International report detailed the harassment and intimidation that Eritrean regime operatives have mounted against regime critics in Europe, Africa and the U.S. In November 2024, The Washington Post exposed, in depth, the regime’s otherwise hidden fundraising operations in the U.S., despite the ongoing imposition of U.S. sanctions against the pertinent Eritrean entities.

Increasingly, the regime’s offenses have come to be characterized by observers as amounting to transnational repression.